|

The

most common type of pre-pro glass stands around 2-1/2" tall, has a

capacity of around 2 oz, has an acid-etched or white-frosted label, and

may or may not gave a gold rim (other common glass types are described

in a Collector's

Guide located elsewhere on this site).

The most notable feature of these pre-pro

glasses is

the thinness of their walls and the often fine quality of the

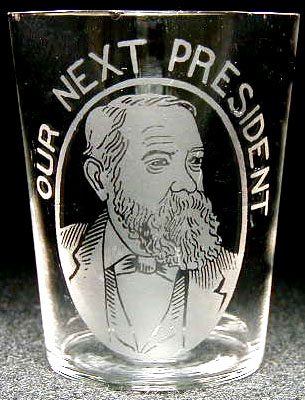

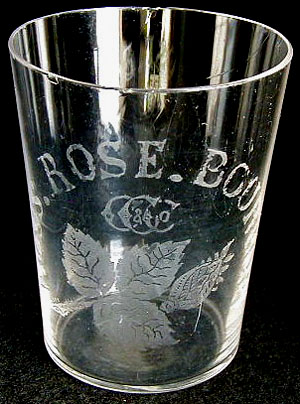

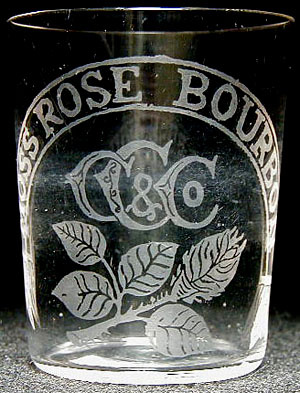

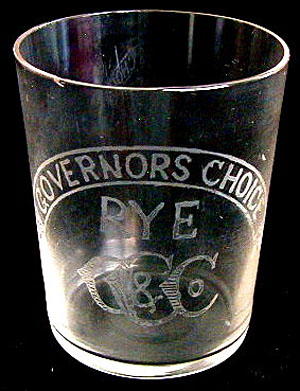

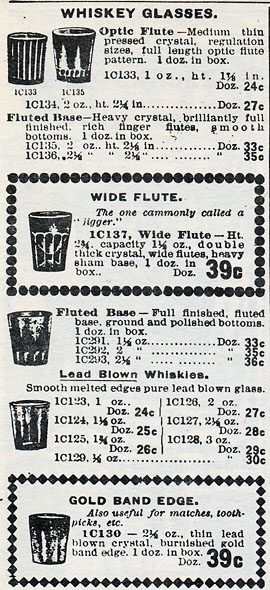

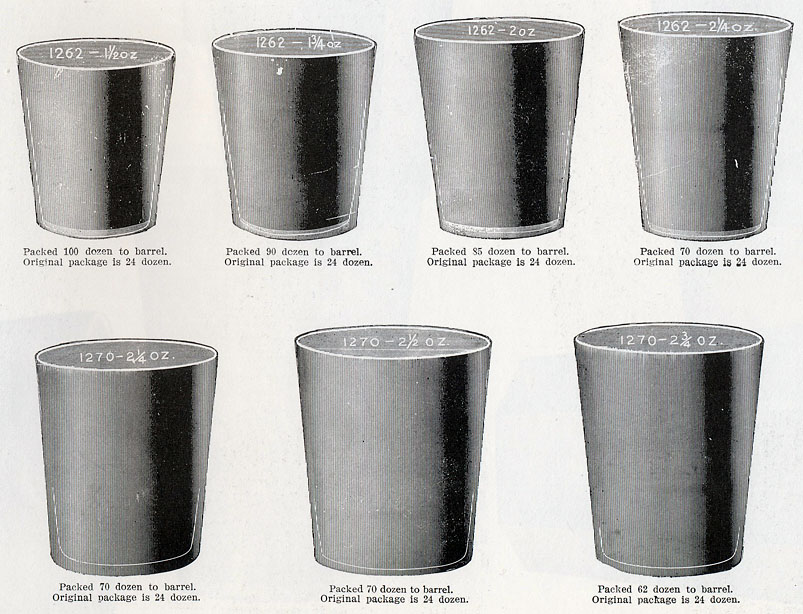

leaded glass used in their manufacture. This type of glass first appears somewhere around 1880, although the very earliest glasses are very difficult to date with accuracy. A handful of souvenir glasses that can be acurately dated to 1893 have been documented (see the shot glass database). By the end of the nineteenth century, however, they were clearly starting to become a common form of advertising. The earliest glasses (typically pre-1900) were blown by hand, which made them time-consuming and expensive to produce. They also had acid-etched inscriptions or decorations, which itself was a laborious and expensive form of labeling. Acid etching involves eroding portions of the glass with caustic vapors or solutions, meaning that other regions must be protected with wax, for example. The expense involved in the production of these early glasses meant that they were impractical vehicles for advertising, although a certain Mssrs Conrad & Co. of St. Louis, MO. seemed to think it worth a try (see examples below). The late 1880s saw rapid advances in glass-blowing technology and in the techniques used in inscribing glass. By the turn of the century, glass-blowing had been automated and machines capable of producing shot glasses and other drinking vessels in large numbers at very low cost were becoming very common. All the major glasshouses offered "Lead-Blown Tumblers", which were sold by the barrel, packed in straw. The examples below are from a catalog distributed in 1903 by The Cambridge Glass Co. of Cambridge, OH. Several different sized shot glasses are offered:

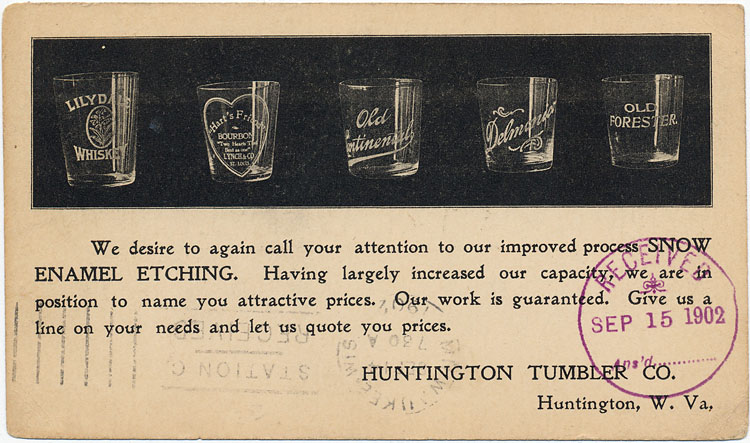

Automation had also reduced the price of labeling a glass. By the turn of the century, George Truog, founder of the Cumberland Glass Etching Works of Cumberland MD., was able to acid-etch glasses at sufficiently low cost that his distinctive work was appearing on a staggeringly wide range of table ware, tumblers, beer glasses and shot glasses, many examples of which survive today. Truog remained one of the few proponents of acid-etching, however, for increasingly glass makers were turning to an even cheaper alternative to apply labels to their glassware. Most surviving pre-pro glasses were inscribed using a rubber stamp and a powdered vitreous material. The glass was refired after the powder had been adhered, causing the vitreous dust to fuse to the wall of the glass, thereby creating an enamel (pre-pro glass collectors use the term "white-frosted") label. These labels were not as durable as acid-etching and often flaked off due inadequate firing or preparation of the glass, but the cost benefits meant that such labels soon became the norm.

The combination of cheap glasses and cheap labeling techinques meant that the early 1900s witnessed a veritable explosion in the number of glasses being distributed. Although one can only guess at actual numbers, it's not unreasonable to think that 20,000 to 30,000 distinct label variants may have have been produced during the shot-glass hay-day. Only around 10,000 of these have been documented at the time of writing. |

Please contact the glassmaster with questions or comments