From wild west towns like Tombstone, Abeliene, and Cheyenne, to the plush salons of New Orleans, Saint Louis, and New York City, rye whiskey was the most popular spirit of eighteenth century America. The thirst for this alcoholic brew traveled as far as the West Indies, France, England, the Philippines, and even China. And the best of the rye was Monongahela Rye, manufactured along the banks of the Monongahela River.

In the late 1700s and early 1800s, the hills and meadows along the Monongahela River were lush with planted rye. The area between modern Belle Vernon and Monessen was known as the best rye growing soil in the fledgling nation. It was here, in small cottage-industry stills, that the best of the famous Monongahela Rye whiskey was first produced.

In the 1790s, almost every farm in western

Pennsylvania had a still to convert the yearly crop into whiskey. The whiskey

was loaded on horses and mules and hauled over the Allegheny Mountains to

eastern ports. Then Alexander Hamilton, Secretary of the Treasury, put a tax

on whiskey to help pay for the Revolutionary War. A hew and cry arose in

western Pennsylvania that not only tested the new constitution, but brought

George Washington back to Pennsylvania at the head of an American army.

Although few shots were fired, the confrontation became known as the Whiskey

Rebellion (Insurrection). One by one the whiskey stills began to shut down.

By the 1800s, the manufacture of

whiskey became a full blown industry as dozens of distilleries grew out of the

hundreds of dismantled western Pennsylvania stills. Most famous of them were

the Sam Thompson Distillery in Brownsville, the Abraham Overholt and Company

Distillery in West Overton, and the largest and best, the John Gibson and Sons

Distillery in Gibsonton.

John Gibson, an Irishman from Belfast, had established a whiskey business in Philadelphia as early as 1837. In 1856, he purchased over forty acres to build a distillery on the east bank of the Monongahela River just north of the modern Belle Vernon Bridge. He intended to manufactured wheat and malt whiskey, in addition to the better known Monongahela Rye.

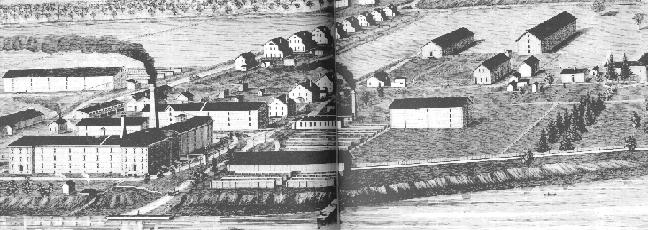

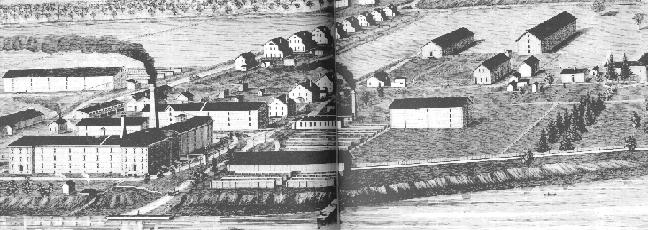

Construction for the new site began immediately. Limestone was hewn out of the nearby Gibson Quarry and the cornerstone was put in place. Extra care had to be taken to assure the bonded warehouses could withstand the weight of hundreds of barrels of whiskey, that the temperature of each warehouse was maintained at 80 degrees year round, and that no artificial light was used. When the contractors were finished, the site contained 8 bonded warehouses, a 4-story malt house, a distillery, millhouse, drying kiln, saw mill, boiler, 2 carpenter shops, a cooper shop, a blacksmith shop, and an ice house. Whiskey was flowing by April of 1857.

The cooper shop is were the oak barrels to hold the whiskey were made. The process was a long one with each stave of each barrel aged three years before the barrel was assembled. Then the barrels were assembled by hand without the used of any nails. One person could make only three barrels a day. Once the barrel was filled with whiskey, it either went into the bonded warehouses, or was shipped to a buyer. Thus a continuous need for barrels kept the cooper shop busy. At its peak, 5,000 railroad carloads of whiskey-filled barrels where shipped yearly from the distillery.

In 1881, a fire destroyed the distillery building and one large warehouse, but they were quickly rebuilt and by 1882, the distillery employed seventy-five people who churned 775 bushels of rye into sixty-five barrels of whiskey each day. It was recognized as the "largest rye-distillery in the state and probably in the Union." Manufacturing now included French brandies, which were blended at the plant in Philadelphia from whiskey shipped from Gibsonton.

In 1883, John Gibson died. His son Henry C. Gibson formed a company with long-time associates Andrew M. Moore and Joseph F. Sinnott. The distillery was then known as John Gibson's Son and Company. Production continued to grow until they produced 20,000 barrels of whiskey a year, consuming 1,500 bushels of rye each day. It was the world's largest manufacturer of rye whiskey.

On December 11, 1882, a cold, cold, day when the river was frozen solid, an explosion rocked the distillery and the ensuing fire destroyed warehouse number one, the distillery, and the malt houses. The buildings were quickly rebuilt and by October, 1883, were open for business again. But on June 2, 1883, a lantern exploded and fire destroyed warehouses numbers 2 and 3. Seven thousand barrels of whiskey were lost.

By 1884, Henry retired. The company name became Moore and Sinnott, and eventually Gibson Distilling Company. A telegraph office was established at the mill in 1877. A post office was created for Gibsonton in July of 1884. The mill converted from coal to natural gas in November of 1893, and had its own water supply-- directly from the river. The number of workmen's houses now counted 150 and 200 men were employed at the plant. They manufactured 150 barrels of whiskey a day at a value of $80 a barrel. The company paid an estimated $750,000 in taxes each year, or $2,000 dollars a day. The community of Gibsonton was thriving. According to George Dallas Albert's History of the County of Westmoreland Pennsylvania printed in 1882, "There is no distillery in America that has such costly and substantial buildings, and none that equals it in the purity and flavor of its whiskeys, which have a world-wide reputation for their excellence."

By 1905, a new seven-story, brick, bonded warehouse was being constructed. According to the Belle Vernon newspaper The Enterprise on Friday, September 8, 1905, "Within the cornerstone was placed a small bottle of old and a small bottle of new whiskey, some silver coin of 1905 mint, an advertisement of Moore & Sinnott, a copy of a Pittsburgh daily paper, and of course, a copy of The Enterprise."

Then came Prohibition. In 1920, the Eighteenth Amendment was adopted. It killed the distillery business in the United States. The Gibson Distilling Company went bankrupt. On Tuesday, September 8, 1923, a sheriff's sale was held and when it was over nothing remained of the distillery except the buildings. The town nearly became a ghost town.

The Pittsburgh Steel Company acquired the property. In 1926, the limestone buildings were dismantled and the blocks were sold at $1.00 a load. People from all over the Mon Valley purchased the stone for their own use. Many a valley building or wall has a bit of the distillery in it. According to The Enterprise, "It is said the Trinity Protestant Episcopal Church of Monessen [688 McKee] will use a large portion of the stone in erecting a building in that city." The newspaper went on to say, "I wonder if these stones, which once housed whiskey, will save as many souls as the contents sent to hell."

----------------

Story by Cassandra Vivian

Illustration: Lithograph

of the John Gibson's Son and Company Distillery in Gibsonton from George

Dallas Albert's History of the County of Westmoreland Pennsylvania