by

Ronald T. Shawhan and Robert E. Francis

cached 5/15/2003: View Current

by

Ronald T. Shawhan and Robert E. Francis

The year was 1786; the place was a farm near Chartiers Creek, a few miles southwest of Pittsburgh; at the time the land was in dispute as to whether it was the territory of the state of Virginia or that of Pennsylvania. The farm, of several hundred acres, belonged to the farmer who was in the huge barn, which held not only grain and other produce, but also contained barrels of aging whiskey. The gentleman was Daniel Shawhan, Jr., born in 1738 in Kent County, Maryland. Daniel was ready to broaden the market for his whiskey, which had become fairly well known in the area, and he pondered what he should use for the brand name. After due consideration he decided to call it "Monongahela Red", in recognition of the fact that he was located in the Monongahela River Valley and his whiskey had a reddish amber color. Thus began a tradition of marketing Shawhan whiskey that was to last into the 1970s.

At the age of forty-eight, Daniel could look back on a life where he was born the first son of Daniel Shawhan, Sr., who had been born in 1709, the first son of Darby Shawhan, Sr. and his wife, Sarah Meeks. Darby, 1673-1736, a Scotch-Irish tobacco farmer, has been recognized as the first Shawhan to migrate to England's American Colonies, settling in Kent County, Maryland in about 1698. Darby and Sarah were married in 1707 and they soon acquired 100 acres from a tract of land called "Shad's Hole" they named their property "Darby's Desire" on which they farmed tobacco, grew fruit trees, and raised sheep, hogs, and cows. They probably also converted some of their fruits into spirits for personal consumption and to use in bartering. After Darby and Sarah's deaths in 1736, the land was managed by Daniel, Sr., who sold it to his brother John in 1740; the family of Daniel, Sr. with his two-year old son Daniel, Jr. in tow, moved to Frederick Co., Maryland. The family stayed there for many years, through the French and Indian War period, in which Daniel, Sr. served in the Maryland Militia, , until 1759, when they pushed further westward into Hampshire County, Virginia (WV), locating near Romney. It was there that Daniel, Jr. met and married the beautiful, Margaret Bell, with "hair like the sunsets, filled with gold and reds".

It was also there that Daniel, Jr. became skilled in the art of whiskey making, learning from his father. The basic process involved first obtaining, grinding, and mixing the grains into a mash in homemade wooden tubs; corn was the predominate grain, mixed with barley, rye or wheat. Malt, yeast, and other fermenting agents were then added, together with a measure of hot, pure spring water. After a suitable period of time to ferment, the resultant brew was ready to be poured into a still to be distilled. A typical frontier still consisted of a pear-shaped copper kettle topped by a detachable head with a tapered neck that ended in a spiral of tubing called a "worm". When the still was fired, alcoholic spirits vaporized upward into the head and through the worm. The worm was immersed in a barrel of cold water, which caused the heated vapor to condense into whiskey. Drawn off through the end of the worm, the liquor was often distilled a second time, or "doubled" to increase its alcoholic content; the finished whiskey was then poured into jugs, barrels, or whatever containers were applicable. The spent "stillage" of mash was saved for livestock feed.

Shortly after the death of his father, in about 1771, Daniel, together with Margaret and their first four children, moved westward, probably on a Virginia land warrant, to the Chartiers Creek area, near present-day Carnegie, Allegheny Co., PA; they were following the footsteps of Margaret's brothers who had migrated to the same vicinity in the late 1760s. Daniel laid claim to 650 acres and began clearing the land and building habitation for his family and livestock. In the Revolutionary War, Daniel may have briefly returned his family to Maryland, during the "Indian Troubles", as he served with a Maryland troop in 1776; he was later listed as serving with a PA Militia organization. After the War, Daniel again resumed his farming and continued to experiment with the distillation of whiskey; he became prominent in the area, enough to have his home listed as a voting location.

Daniel finally returned home to resume his life as a farmer and whiskey distiller. His "Monongahela Red" was soon a success, but Daniel became worried about the value of his Virginia land warrant in the dispute with Pennsylvania, and the increasing burden of the whiskey taxes that the newly established American government had instituted for revenue. The history books call it "The Whiskey Rebellion" and it is an ugly chapter in the first difficult years of the newly formed United States. The presenting problem was the call by some legislators for an excise tax to be placed upon the sale of whiskey. The western states, particularly western Pennsylvania and the Allegheny region of Virginia, did not take kindly to what they considered unfair taxation. However, as is always the case with volatile issues of this sort, much deeper problems lay beneath the surface. For these westerners, life on the edge of the frontier was, at best, dangerous and, at worst, a matter of sheer survival. For us today, it is difficult to imagine the terrible conditions under which the early settlers endured. It is easy to understand why average Pennsylvanian had little sympathy for the new government's need to collect revenue. From his perspective, the government was doing little to protect its citizens on the frontier and, to add insult to injury, it sought to tax one of the few profitable commodities produced in the wilderness. The so-called Whiskey Rebellion reached a head in 1794 when President Washington sent in troops to quell the opposition. Ironically, the excise tax was overturned several years later by President Thomas Jefferson.

In 1788 he uprooted his family, leaving his eldest son, Robert, behind, and traveled down the Ohio River on flatboats, loaded with household furniture, livestock, and other necessary items, including his millstones and copper still their destination was the Kentucky District of Virginia. He landed in Limestone, present-day Maysville, KY, and made his way inland, until he found the type of land and water he sought, settling near Hopewell (Paris) and Ruddles Mill, purchasing 130 acres from Reuben Rankin this was in Bourbon County, which had been formed in 1785. Family tradition holds that he found a big spring gushing out of a low limestone bluff, along Townsend Creek. "Daniel Shawhan, stopped at the spring back of Mt. Carmel Church, decided it was the best water he ever tasted and that he would build a distillery on the spot, which he did."

Daniel soon had his land cleared enough to begin growing the corn, rye, and other grains typically farmed at the time; he also quickly had his still in operation. Available evidence indicates that his still and distillery were located just off of a spring behind what became Mt. Carmel Church. The abundant pure water and fertile soil soon provided the Shawhan family with a handsome harvest of grain and a functioning distillery. Daniel continued to test and experiment with his whiskey, based on the excellent grains and limestone waters available to him. His formula, as perfected, rendered with volumes, times, and temperatures, provided the signature that distinguished Shawhan whiskey for generations to come. It is unknown as to the exact combination of grains used by Daniel in his formula, but a popular mix was 75% corn, 15% barley, and 10% rye. Daniel was very particular about his yeast culture, perhaps using the same one he found so successful in Pennsylvania.

He and his sons recognized that the market for their produce, including their whiskey, prepared by the family's secret formula, could reach as far as the port of New Orleans, which could be reached by travel down the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers. Together with other early Bourbon County pioneering distillers, such as Jacob Spears, the Ewalts, and Bedfords, Daniel would ship his whiskey, stamped Bourbon County, to New Orleans where it soon became prized for its smooth taste it became known by the generic name of "bourbon whiskey". The Shawhan sons often made the trip on flatboats to New Orleans, returning with Spanish doubloons jingling in a satchel across their shoulder.

No one really knows who originated bourbon whiskey. Traditionally, the Reverend Elijah Craig has been credited as the "father" of bourbon whiskey. While it is true that the good Baptist Reverend was in fact a whiskey distiller in Kentucky during the late eighteenth century (perhaps as early as 1789), no evidence exists that he was the first to make it. Sticklers on the subject content that old Elijah didn't even live in Bourbon County (he lived slightly to the west of the border); however, this does him a disservice. He did, in fact, distil bourbon whiskey and sell it down in New Orleans by that name.

Daniel Shawhan, Jr., is a clear candidate for honors as the first bourbon whiskey maker. He was already distilling whiskey by the time Elijah Craig established his business. However, the more likely candidate is Jacob Spears, a neighbor of Daniel's who arrived in Bourbon County in 1787. Sadly, the Shawhan name is not remembered by historians except as a footnote of the Whiskey Rebellion. Jacob Spears is mentioned but only in passing.1

Daniel, Jr. died in 1791 and his sons continued to operate and manage the family farm and distillery into the 1800s. A government record shows that John Shawhan owed the Government $84.05 on June 20, 1794; it listed the distillery in Bourbon, County, Kentucky.

A local Bourbon County, Kentucky, newspaper of the late 19th century ran a lengthy article on the establishment of the Shawhan family whiskey distilling business. It is presented here in it's entirety (the reader is cautioned to read the article with a bit of a critical eye because some of the historical data is incorrect). From the Paris True Kentuckian dated November 11, 1874:

BOURBON WHISKEY

When, Where and by Whom-First Distilled

How the name "Bourbon" Originated.

It was during the latter part of Washington's last Administration that the noted Whiskey Rebellion of Pennsylvania took place. At that time the mountain recesses of the Alleghanica, west of what is now known as Cumberland Valley, was the great whiskey district of the country. It was very sparsely settled. All the grains that were grown, save a scant supply for provender for the live stock, and food for the inhabitants wee distilled into whiskey upon what is known now as the "sour-mash" hand-made, copper-distilled" plan. Soon a large demand for these whiskies sprung up in Philadelphia and Baltimore, and the supply being limited a ring wee formed a "corner" made, and the goods put at high figures. The National Government, then as now, was hard pressed for revenue. Repudiation was then staring it in the face, and it was without money at home or credit abroad. A happy thought struck the Congressional delegation from New England. It was-as it would not tax their constituents a dollar- to levy a tax of $500 on each still that was used for manufacturing spirits. Their ideas were enacted into laws. The following season revenue officers were sent out from Washington to assess and collect the tax. The distillers previously met, formed a union, and upon the arrival of the officers defied them to put their laws into force. The officers upon their arrival in the insurrectionary district, seeing that they could not execute the law, and fearing the loss of their lives, returned in haste to Washington. By this time the season was far advanced, and it was decided, upon the part of the authorities to await for the-beginning of the next season before again attempting to enforce the collection or the tax. The following Fall the officials backed up, then as now, by the ever ready "troops," set out on their mission again. They arrived at the anticipated scene of their troubles in due time, but they met with an unexpected disappointment. The distillers had decided that there was to be no more distillation until the law was repealed. The officers after having marched up the hill marched down again. Thus ended the rebellion.

Many of the old frontiersmen tired of being harrassed in front by the government and the rear by the Indians, determined to plunge boldly into the then unexplored wilderness beyond the mountains. Among this number was a man by the name of Shawhan. He had a large family, was well-to-do, and packing everything moveable that he had that was necessary for such a lifelong expedition into a wagon, he set across the mountains. He took along with him the cause of his removal, the "still". Two months later (this was about the Fall of 1796), he and his family, consisting of his wife and several children, were busily engaged in distilling in Bourbon county, Ky., on Townsend creek, erecting temporary cabins to shelter them during the winter. The country was full of wild animals, and still wilder Indians. It was twenty miles to the nearest fort.

By tact and skill they avoided coming in contact with the savages. When the long winter in the wilderness was over they, having in the meantime cleared a few acres, planted a patch of corn. An abundant harvest greeted their labor, The "still" having been erected, it was put into operation and then it was the first whisky ever manufactured in Kentucky, or in the Mississippi Valley, commenced.

In Pennsylvania they called whisky "Monougahela," it being called after the county in which it was manufactured. Shawhan, following the same example, called the whisky manufactured by him after the county in which his new home was situated, "Bourbon."

The third year out the father died, and it then devolved upon his son Joseph to carry on the business. He being industrious, their little farm was soon extended, and assumed respectable size. The excellency of his whiskies soon gave him a wide reputation, and the large emigration kept up a heavier demand than could be supplied. He though, bent his energies to his work, increased his capacity as a distiller, and "Bourbon" soon became a household word. Joseph Shawhan recently died at the age of 85. He left property valued at upwards of a quarter of a million of dollars. (The emigrant from Pennsylvania was Daniel Shawhan, father of the late Joseph Shawhan, who died at the age of 90 years, from being thrown from a horse. At the time of receiving the injury he was quite vigorous, and in the enjoyment of good health, looking as if he might live many years. His relatives still produce the same quality of hand-made fire copper and Bourbon as originally. T.E. Moore, who married Joseph Shawhan 's granddaughter, in connection with his partner, H.C. Bowen, is largely engaged in the distilling business at Shawhan, Bourbon county, as is also Mr. J. Snell Shawhan, a grandson of Joseph Shawhan, and many others in Bourbon, which still maintains her reputation for distilling pure Bourbon and rye whiskies.-ED KEN.).

Daniel III (1765-1840) sold his interests and moved to the Indiana Territory in 1825, leaving the distillery operation to his brothers John (1771-1845) and Joseph (1781-1871), who were quick to capitalize on the opportunities offered.

Both brothers became quite wealthy and well-known prominent citizens; both served in the War of 1812. Joseph lived some ninety years before he was accidentally killed while returning home from the Lexington races, when his horse shied and he was thrown off. Joseph became the largest landowner in Harrison County, with over 3500 acres including a half-mile track on which he would train his racehorses. He also served in the Kentucky Legislature for several years.

They established Shawhan Station, a small community on the Kentucky Central Railroad, from which they could ship their barrels of whiskey and other produce. It also served as a shipping point for other distilleries in the vicinity, such as those operated by H. C. Bowen, Samuel Ewalt, and Gus Pugh. A former resident has written:

"The boundary (of Shawhan Station) was from near Ruddles Fort to the Mt. Carmel Rd. There were tollgates at Larue Rd, Ruddles Mills, and Cynthiana and Paris Rds. We have had changes in our roads and railroads, First a R.R, crossing signal, then a wooden bridge over the R.R., and now a concrete bridge. We once had two stores, a barber, garage, depot, a post mistress, a telegraph operator, 2 coal operators, a section foreman, doctors, school house, church, loading shoots for shipping cattle, and a slaughter pen. The Masonic Lodge and Granger met upstairs at one store. The blacksmith operator was Dick Doty, Coal Operators were Arthur Hendricks and R.R. Lail. The Ticket Agents were John Kiser and V. C. Price. The Section foremen were J. W. Farmer, Harrison Dean, and William Owens. Post Master was Ed Ralls, Mistress was Mrs. Joe Smith. We once had a small dance pavilion where music was furnished by banjo and violin. We have no street names, but nicknames such as "Tin Can Alley", "Frogtown", and "Cedars". Shawhan was settled about 1790. Uncle Joe Shawhan (Joseph, 1781-1871) told of a Spears Distillery in 1790. Shawhan was settled in about 1796. The settlement of Shawhan is near the present-day Harrison County line, and many residents are on Harrison County mail routes. An early church which was the hub of the community has been revitalized and is located along the old Kentucky Central Railroad, later acquired by the L & N R.R. Shawhan was named for the James (Daniel) Shawhan family who traveled from Pennsylvania in a covered wagon, bringing his copper still. The corn harvest was great and he manufactured the "Bourbon" whiskey. He settled on the Townsend Valley Road and later had his still near Shawhan up the old railroad."

Note: The little town of Shawhan, KY still exists (in 1998); it lies about 65 miles south of Cincinnati, OH, between Cynthiana and Paris, KY, off of U.S. Route 27. The General Store, the old railroad depot, a warehouse, and the stonewalled church are its most visible buildings.

John and Joseph expanded the distillery operation, in both Bourbon and Harrison Counties, bringing their sons and sons-in-law into the business, including Daniel Shawhan, (1801-1860), John Laughlin Shawhan (1805-1868), Henry Ewalt Shawhan (1805-1882), and John Shawhan (1811-1862). Grandchildren and their spouses were also brought into the distillery business, including Thomas E. Moore (1831-1921), who married Sarah Shawhan, Joseph's granddaughter.

John Snell Shawhan, one of Joseph's grandsons, was operating a Shawhan Distillery, located about one-half mile west of Shawhan Station, in Bourbon County as late as 1882. It produced "Sour Mash Copper Whiskey", the brand showing "Pure Hand Mash Fire Copper Whiskey from J. S. Shawhan, Distiller, Shawhan, Bourbon Co., Kentucky". In 1881 he produced 232 barrels. In October 1882, it shipped only three barrels, but had 660 barrels in its warehouse. In 1883 it did not operate because of a dry season. On occasion, John Snell partnered with T. J. Megibben; Megibben had purchased a distillery from Shawhan and Brandon in 1850 it was located in Harrison County and had been called the Excelsior Distillery at the time.

As noted, the Shawhans would go into partnership with other distillers, such as H. C. Bowen and the Megibben family, but at all times, the Shawhan formula for making whiskey was kept strictly secret.

By the end of the Civil War, the scarcity of water and the poor grain harvests in Bourbon and Harrison Counties reduced the number of distilleries dramatically. It was time for Shawhan whiskey to be produced elsewhere.

Sarah Shawhan, (1842-1911), was the daughter of Daniel Shawhan, (1801-1860), a distiller known as "Casher Dan" as he paid everything in cash; in 1858 she married Elkin Lightfoot. Immediately after the War, in 1866, they moved to Missouri, outside of Kansas City, in Jackson County, near a little town called Lone Jack. They were soon followed by the family of Charles Redmon Shawhan, and by John Thomas Shawhan, two of Sarah's brothers on February 20, 1870, John married Julia Florence Daniel, daughter of one of the early settlers in the Lone Jack area. In 1872 they were joined by yet another brother, George Henry Shawhan, (1843-1912).

George Henry was a Confederate veteran of the Civil War, having been a member of General John Hunt Morgan's Calvary during its raids into Indiana and Ohio; John Henry was captured during the Ohio raid and was kept a prisoner at Camp Douglas outside of Chicago. After the War he tried to resume farming and distilling in the Shawhan tradition, but experienced difficulties; when he heard from his siblings about the fertile soil and water potential around Lone Jack, he decided to join them, bringing his wife, the former Mary Tatman, and two young children with him. He also brought his mother, the former Minerva Redmon (1807-1890).

Lone Jack, Missouri, was named after a large black jack tree that stood for decades on the ridge of prairie that divides the waters of the Missouri and Osage rivers, until it finally died in 1861. During the Civil War, its citizens were generally supportive of the Confederacy, as most of them had come from the states of Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee. Being close to the borders of Kansas and Missouri, the countryside saw its share of vicious guerrilla warfare from both sides. On August 16, 1862, it was the scene of a bloody battle between Union forces and the Confederate troops of Quantrell. Many of its buildings were burned and its citizens suffered greatly. The battle waged for four hours of artillery fire and hand-to-hand combat before the combatants withdrew from the town. About eighty were killed on each side; they were buried in trenches, one for the Federals and a separate one for the Confederates, near where the old "lone jack" tree was formerly located.

George Henry quickly purchased a farm, built a pond, and began work on his distillery. The Shawhan family whiskey tradition was embarking on a new chronology:

1872 Arrival of George Henry Shawhan in Lone Jack, Missouri, moving from Bourbon County, Kentucky. George Henry was a powerful man, standing 6 foot, 5 inches, and weighing about 250 pounds. It was said that he could raise a 400 pound barrel of whiskey to his lips for a sip to test its flavor.

1873 - By early 1873, George Henry had completed his first distillery, with a capacity of about two barrels of whiskey of forty-two gallons each. It took about one bushel of grain to produce 3.7 gallons of whiskey. The newly distilled whiskey was placed in a warehouse for aging. Steam furnished the power for the distillery and water was drawn from a large pond; the pond also served as a swimming hole and as a baptistery for the Christian and Baptist Churches. The distillery employed a boilerman, distiller, and various others to weigh the grain, and work in the gallon house to fill bottles as they were bought.

1876 August 10 - Mr. B. B. Cave bought 45 96/00 gallons of whiskey, costing $91.80, on account.

1878 Peach brandy and other fruit liquors were added, and orchards were established accordingly.

1880 On September 19, while applejack was being made, the still blew up. A coil became stopped up with the apple pumice, and when the boiler pressure was increased to clear the coil, it exploded employees Daniel Perrow, his son, Will, and Tommie Lester were killed. Six others were seriously injured.

1881 August, Preacher Cunningham paid $9.65 in cash for a keg of peach brandy that he had purchased in Nov. 1880.

March 21, John Quick and his wife commenced work for one year, to be paid $275.

1883 George Henry has three large tobacco barns where tobacco grown around Lone Jack is dried, graded, and made into plugs, sack tobacco, and cigars. His prices were modest you could buy 25 pounds of Gold Nugget tobacco for $8.75, 50 Adigo cigars for $2, and 15 pounds of Licorice Twist tobacco for $6.

1898 On November 6, the saloon owned by George Henry in Kansas City, at the corner of Missouri and Oak Streets, had a record business day. On the same day, his daughter Sally Shawhan, who had married Homer Rowland, celebrated the birth of a son; at Grandfather George Henry's command, the child was named "Record Rowland".

1900 In January, at midnight, the distillery caught fire and burned down. The fire was caused by a defect in the wall around the boiler. The warehouse was not touched it held about 800 barrels at the time of the fire. Federal Records in Missouri identified this Lone Jack, Jackson County distillery as No. 59.

George Henry moved quickly to maintain his

distillery business despite the Lone Jack fire. He went to Weston, Missouri, in

Platte County, and purchased the Holladay Distillery, which had been established

there in 1856 by the brothers Major Ben Holladay and David Holladay. Located

near the limestone bluffs of the Missouri River, it had access to a wonderful

spring, producing some of the purest water to be found, drawing the comment from

George that using that water with his formula he could "beat the Bourbon County

fellows all hollow." The property includes a cave within which whiskey was once

aged. In Federal records it was registered as No. 8. At the time, Distillery No.

8 was not distilling, but spirits were being drawn from its warehouse.

George Henry moved quickly to maintain his

distillery business despite the Lone Jack fire. He went to Weston, Missouri, in

Platte County, and purchased the Holladay Distillery, which had been established

there in 1856 by the brothers Major Ben Holladay and David Holladay. Located

near the limestone bluffs of the Missouri River, it had access to a wonderful

spring, producing some of the purest water to be found, drawing the comment from

George that using that water with his formula he could "beat the Bourbon County

fellows all hollow." The property includes a cave within which whiskey was once

aged. In Federal records it was registered as No. 8. At the time, Distillery No.

8 was not distilling, but spirits were being drawn from its warehouse.

1901 G. H. Shawhan was withdrawing whiskey from Warehouse No. 59 at Lone Jack, but was not distilling there.

1902 - the George H. Shawhan family was occupying a beautiful home in downtown Weston, Missouri.

Note: In 1998 the home is a Bed & Breakfast, called the Benner House, located at 645 Main Street, in "Historic Weston". It advertises itself as a "fine example of steamboat gothic architecture", originally built by "Mr. George Shawhan, who owned what we know today as the McCormick Distillery." It's a picturesque 2-_ story Victorian-style home, with a wrap around porch on both the first and second floors. It features: "The main parlor provides an especially inviting atmosphere for conversation and getting acquainted. Slip away into the sitting room where you can curl up in a rocking chair with your favorite book. Enjoy a full candlelight breakfast in the Victorian dining room."

1903 G. H. Shawhan was still withdrawing whiskey from Warehouse No. 59 at Lone Jack.

George Henry maintained a correspondence with other Shawhan family members. A copy of one such letter, dated in 1903, has been found. It was written on Shawhan Distillery Company stationary. "IT KEEPS ON TASTING GOOD" was printed across the top. Arched across the top is "THE SHAWHAN DISTLLERY COMPANY", appearing in bold and shadowed capital letters. Slightly below this is a picture of a tree flanked on both sides with a picture of two large kegs. The keg on the left has a stalk of corn arched around both sides of its head. On the Keg-head are these words, "SHAWHAN Old Style Sour Mash Formula established 1786". The keg on the right is surrounded by two stalks of rye. Printed on the keg-head are the words, "HOLLADAY pure Rye Formula Established 1849." The body of the letter is written in pen and ink. The text reads verbatim:

Your letter of the 10th came to hand yesterday and was glad to find some more kinfolks. Daniel Shawhan who moved to Bourbon Co., Ky. In 1786 was my Great Grandfather so was he to you. My Gran Father was John Shawhan a brother of your father's father. There were several of them Jos., John, Robert, George, and I do not remember the others. I find two of our great uncle Robert's boy's Gran sons one in Iowa and one in Nebrask they have both written me but I have not got the letters here. I can't remember the towns that they are at but will try and look it up. You failed to state which was your Gran father and also what your father's name was. My father's name was Daniel and Gran father was John. Our Great Gran father died in Bourbon Co. in 1791 and was only 56 years old. First man to make whisky in Bourbon Co., Ky and was the originator of Bourbon Whisky. He made Whisky in Monongalia Co., Virginia under Washington administration. I do not know how much sooner than. My Granfather made it and my father and I have been making it for over 30 years.

1904 Geo. Shawhan withdrew his last whiskey from Warehouse No. 59 at Lone Jack, upon payment of tax. The products of his distillery are marketed by the Morrin-Powers Mercantile Company of Kansas City.

1905 The Shawhan Distillery promotes a whiskey labeled "SHAWHAN Four Generation Rye WHISKEY"; the four-generation label shows pictures of the Shawhans involved, with dates Daniel (1786), John (1826), Daniel (1854), and George (1904).

1907 The last distillery purchased by the George H. Shawhan family was the Spring River Distillery at Verona, Missouri, registered as Distillery No. 6. It was managed by R. G. Baker, who had married Sarah Shawhan (daughter), and J. O. Tong, who had married Lorena Shawhan Lackey (granddaughter) of George H. Shawhan. Note: This distillery was sold in 1918.

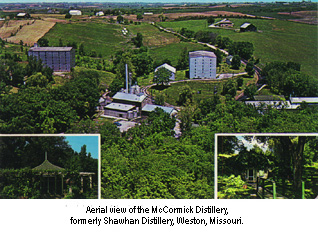

1908 George sold his Weston distillery facility and the Shawhan brand name, but absent the family formula, to the Singer family. The Singers purchased the McCormick name from the McCormick family, which owned a distillery but had abandoned plans to continue making whiskey. The Singers resumed production after the end of Prohibition, using the original McCormick recipe. They later sold the facility and the whiskey aging in the warehouses, in 1947, to Dr. Armand Hammer of United Distillers; he did not continue production. In 1951 the Cray family bought the facilities and production was under way again.

Note: In 1998, the Weston, MO location is still known as the McCormick Distillery. Private investors presently own it; employees also have a financial interest in the ownership. The distilling facility itself has not been in operation since the 1980s; McCormick obtains its whiskey from other distiller suppliers. There was a time when the McCormick Distillery was well known for its ceramic whiskey containers, featuring such popular figurines as one of Elvis Presley.

1912 George Henry Shawhan died; he's buried in the Lee's Summit Cemetery.

1975 On Thursday, June 5, 1975, the Kansas City Star ran a full page story titled "Distiller Matched Brew's Power". Covering Jackson County history, the article described the George Henry Shawhan Distillery operation in Lone Jack. It featured an interview with Record Rowland, the same Record Rowland who had been born on Nov. 6, 1898 and had been named "Record" in recognition of the record business day that was experienced by a George Henry owned saloon in Kansas City on the same day. Excerpts from the article follow:

"A man who could raise a 400 pound barrel of whiskey to his lips for a drink obviously had a liking for the fermented liquid. Not only did George H. Shawhan enjoy the taste of whiskey in moderate amounts he derived as much pleasure in making the alcoholic beverage in his distillery at Lone Jack.

"In 1872 Shawhan moved to Lone Jack from Bourbon County, Kentucky, where his family had operated distilleries since after the Revolution War.

"The original plant was just east of what is now the central intersection in the village of 199 persons where Lone Jack, Lee's Summit, and Bynum Roads cross. Today just the spring-fed pond surrounded by brush remains, but for more than 20 years local corn and grain were processed into thousands of gallons of bourbon whiskey, straight whiskey, rye whiskey, and white corn whiskey under the watchful eye and demanding taste of Shawhan.

"His great-grandfather, Daniel Shawhan, is credited with naming bourbon after the Kentucky county where he first made it.

"Record S. Rowland, Shawhan's grandson, says flatly that Lone Jack whiskey was 'the best.' Rowland, of 4010 Prospect, recently displayed what he says is the only copy of the old family recipe dating from 1786. A simple listing of amounts, times and temperatures were followed to the letter by Shawhan with frequent testing of taste and smell as the whiskey developed, Rowland said. 'Many a time I've seen him taste whiskey in the warehouse but he always spit it out,' Rowland said. Rowland said that he had seen the 6 foot, 5 inch, 250-pound Shawhan take a full barrel, lift it by the chimes (the rim formed by the protrusion of the staves beyond both ends of the barrel) and drink from the bunghole.

"Once while taking four barrels of whiskey to Pleasant Hill south of Lone Jack in Cass County the tailgate of Shawhan's horse-drawn wagon came loose and the barrels rolled off, Rowland said. Shawhan reloaded the whiskey by himself without waiting for help, but he dislocated a shoulder while wrestling the big kegs onto the wagon, his grandson said. After he made the delivery and returned home, Rowland said, it took two men tugging on Shawhan's arm to pull his powerful shoulder into place.

"'Grandpa was a person that always watched his temper,' he said, 'but he was a very powerful man. He drank only three toddies a day and nobody could make a toddy like he could,' Rowland said. 'He would get his sugar and water dissolved first and then add whiskey. Then he would usually go out in the kitchen and see if they were baking pies or something using fruit. For instance, if they were making a cherry pie, he would put some cherry juice in the toddy called it "cherry bounce"'.

"Rowland said his grandfather had a saloon at Missouri and Oak in Kansas City as well as the distillery. On Nov. 6, 1898, when Rowland was born at 728 Cherry, the tavern did a record day's business. 'We'll just name him Record,' Grandpa said, 'and what Grandpa said was law and order,' Rowland said.

"In addition to the distillery and saloon, Shawhan had a 'gallon house' in Lone Jack as well as a plant where plug tobacco was compressed. The gallon house sold liquor in crock jugs and barrels in amounts more than a gallon and less than five gallons, as required by law of the time. The gallon house sold whiskey for home consumption, Rowland said, 'In those days everyone had a place for a barrel of whiskey under the stairs (of their home).'

"Saloons bought the whiskey in barrels and then transferred it to heavy gals bottles called bar bottles. Rowland's cousin, James b. Shawhan, of Lee's Summit, has one of the 2-pound bottles with "Shawhan Whiskey" on it in gold lettering. 'You see in the movies where they hit somebody with a whiskey bottle from the bar. If they had hit somebody with one of these it would kill them,' Rowland said.

"Lone Jack whiskey was advertised to treat its consumer well. 'It keeps on tasting good', old advertisements proclaim.

"The distillery in peak production turned out 42 gallons of whiskey daily with one bushel of grain producing 3.7 gallons of whiskey. This was an official ratio set by the federal government for taxing the distiller. If the distiller only managed to produce three gallons of whiskey from a bushel of grain he still had to pay taxes on 3.7 gallons of whiskey, Rowland said, and if more than 3.7 gallons of beverage were distilled from a bushel the whiskey-maker had to pay a higher tax.

"The whiskey was sealed in a government controlled warehouse after it was barreled, he said. "When that whiskey came out of the distiller when it came out of the copper tubing that no longer belonged to the distiller." A government employee measured both the amount of grain used in distilling and the amount of whiskey put in barrels to double-check the amount of tax owed. Until the tax was paid it remained under government key, Rowland said.

"To make 100-proof bottled-in-bond whiskey Shawhan would put whiskey in new oaken casks (made at the Bentonville Cooperage Company, Bentonville, Ark.) for four years. The whiskey was poured into the barrels at 101 proof (about 50.5 per cent alcohol). But because the wood absorbs water and not alcohol, Rowland said, during the aging process the whiskey would rise to 106 to 108 proof. Water would then be added to bring it down to 100 proof after 48 months in storage. Now whiskey is distilled at 120 to 130 proof to cut down on space during storage, Rowland said. 'They've ruined whiskey,' he said. 'It's just like if your wife makes a big batch of vegetable soup and then evaporates it down to canned soup consistency and then adds water to bring it back to where it was, you've lost all your flavor.'

"Whiskey flavor was checked for both taste and smell, Rowland said. 'Distillers would wash their hands with unscented soap, he said, and then rub their hands together vigorously until they were very dry. Then they would pour a drop of whiskey in their hand and smell it.' He said, demonstrating by cupping his hands over his nose and inhaling sharply.

"The 'bull tail' also was an important quality control tool during the fermenting stage, he said. The bull tail was a length of rope attached to a wooden handle. The rope would be lowered into a vat of fermenting grain and then pulled out. The hemp acted as a strainer, letting the alcohol drip off the end of the rope while the mashy grain would remain stuck on the bull tail. "Some times those guys would get pretty high on that bull tail," Rowland said.

"Rowland and his cousin, James B. Shawhan, have relics from the distillery. They include brass stencils for painting the type of liquor and the distiller's name on whiskey kegs and a curved knife with a handle on each end of the blade for scraping out barrels after they had been used to age whiskey. One momento is a small one-forth pint bottle with the Shawhan label on it. These containers were called "eye openers" or "nightcaps", depending on when they were consumed. In the bottle is whiskey distilled in 1904 and bottles in 1908 after aging. Another bottle empty has a label with the picture of four generations of Shawhan distillers.

"A hotel in downtown Lone Jack that was the center of a Civil War battle was converted by Shawhan for a home for his wife, Mrs. Mary F. Shawhan, and their children.

"Shawhan operated the distillery in Weston until 1907, when he sold his interest there and operated a distillery in Verona until his death in 1912, Rowland said.

"A list of recommendations and advice from the Shawhan distillery states "Good whiskey is a product which is naturally and necessarily pure, sterile, and antiseptic. Every physician prescribes it. No household should be without it."

"Shawhan, however, concluded his advice on liquor consumption with "Don't let whiskey get the best of you get the best of whiskey. Shawhan is the best of whiskey."

Kansas City Journal article of June 27, 1975, by Dorothy Butler titled "Lone Jack Once Famous for Its Whiskey and Tobacco" is as follows:

"This is a beautiful little hamlet, but for that damnable distillery over there" said the irate visiting minister of the Christian Church of Lone Jack disdainfully flung his hand in the direction of the Shawhan distillery. In the congregation for the first and only time he entered the church sat George Shawhan, giver of the land for the church, rocks for its foundation, and money for its erection when the till got low. He had come to the dedication of the church. He was the owner and operator of the distiller, and not being a church goer had been begged into attending the dedication of the church he had liberally benefited. He was only amused at the preacher's indignation.

"George Shawhan had grown up with the distillery business. His great-grandfather Daniel (1736-1791) had distilled whiskey in Monogalia (sic) County, Virginia, now West Virginia; in the late 1700s and called it Monogalia Whiskey.

"Soon after the Revolutionary War the government collected excise tax on distilled whiskey, and this was the signal for the Shawhans and other distillers to move West. Daniel and Margaret and their family settled in Bourbon County, Kentucky in 1784 beside a limestone spring, and began again to distill whiskey from the secret Shawhan formula, but because corn was scarce rye was added and accepted by the trade. This was the first still in Kentucky, and Daniel called its product 'Bourbon' after the county.

"Here for almost one hundred years, Daniel, followed by his son John (1771-1845), and then his grandson Daniel ( 1801-1860} ran the Shawhan distillery.

"Shortly after the Civil War, in 1868, members of grandson Daniel's family settled at Lone Jack, soon to be followed in 1872 by George and Mary (Tatum) Shawhan, and the mother, Minerva Redmon Shawhan.

"George had fought in the Civil War under Morgan. He bought a farm near Lone Jack, built a pond sand distillery. The pond became the swimming hole for the boys of the community, and the baptistry for the Christian and Baptist churches.

"The distillery employed a boilerman, distiller, and a man to weight the grain. In the gallon house were three or five men who filled the bottles as the liquor was bought. According to the Kansas City Journal of June 27, 1901, Uncle Sam kept 'a vigilant eye on the whiskey distiller. His agents practically run the shooting match. The distiller is allowed to make the whiskey, but not to touch it. A government storekeeper and gauger weights the grain into the bings, weights it into the hopper, and keeps a lock on everything from the time the raw material goes in until the distiller pays the government tax.'

"The capacity at first was two barrels of whiskey or 42 gallons each per day, but was later increased to three barrels. There was an excise tax of $1.10 per gallon on the (?) gallon whiskey. Peach brandy was added in 1878, and in 1879 George set out a 10 acre peach orchard.

"We spent a day going through the account books of the distillery at the Jackson County Historical Society files in the Jackson Square Courthouse: we picked out names that were familiar in this locality so that readers could determine if their ancestors took advantage of the products of the Shawhan distillery and tobacco factory.

"The old account books indicate that B.B. Cave bought 45 96/00 gallons of whiskey on August 10, and again the same amount on October 2, 1876, each deal costing $9l .80. In August 1877, he bought 43 26/100 gallons, and paid the last of his account by selling corn sheller to the distillery for $80.02. Dr. Edward Ragsdale's account is in one of the three account books. He is the doctor who cared for the wounded at the Bottle of Lone Jack in 1862.

"Others mentioned were William Johnson, Oak Grwe, $31.07; G.W. Tate, Lone Jack. $276, $221.65 and $75; R.M. Steele and J.W. Locke, Oak Grove; J.B. Keshler, Grain Valley; C.C. Bradley, Sni Mills; D.K. Murphy, Greenton.

"Preacher Cunningham paid $9.65 cash in August 1881 for a keg of peach brandy that he had purchased in November 1880; Van Cleave & White, Lake City; Daniels and Parker. Grain Valley; W.F. Thomas, Blue Springs; John Garby, Oak Grove merchant, bought eight barrels in 1877 on account, making the final payment by 'credit on mill.'

"Traded on account were onion sets, 20 pounds of pork $1; 11 pounds pork at $.05/pound, and a load of wood, $1, as listed on page 107 of one of the account books. Other items listed in 1879 were 1/2 load corn $4.30 pounds beef at $.05, $1.50; 30 pounds beef at $.065, $1.95; 15 bushels apples et $.50, $7.50; 5500 shingles at $3 per thousand, $16.50; 2 pounds yarn $1.75; 1 coat $6; 1 blouse $2.50; 100 feet lumber $1.50; 13 pounds sugar $1.82; 1 dozen brooms $2.25.

"James Rolf hauled from Thomases 29 1/4 cords of wood on Jan. 31, 1880, and worked for 58 days at $39.20. On April 15, 1879 $10 was paid to Hammond for a "hoss." Hammond worked for 11 months in 1877 for $16 a month; and seven and a half months in 1879 for $120. John Quick and wife commenced work on March 21, 1881 for one year at $275, another item reads. There was a toothbrush charged to Mrs. Quick on this account at $.25, so there was apparently more than liquor sold at the store.

"The Shawhans also had three large tobacco barns where tobacco grown around Lone Jack was dried, graded, and made into plugs, sack tobacco and cigars. At times merchants would trade goods for their supply of tobacco. J.E. Perkino at Sni Mills paid $11.75 in merchandise in 1885; a case of assorted nuggets were delivered by wagon to A. Roush at Strasburg, 1883; J.W. Minter, Oak Grove, bought a 10 pound sack of smoking tobacco in August 1883; Hull and Co., Oak Grove, bought 25 pounds gold nuggets at $.35, paid $1.50 by canned qoods and $4.58 by check.

"The selections of tobacco were wide and the prices low - judging by today's prices - 25 pounds Gold Nugget $8.75; 15 pounds sack smoking, $6; Lone Jack Twist $4; Sweet Twist $5.S5; 10 pounds Grange Rolls $4.20; 50 Adigo Cigars $2.50 Prize Bull $1.75The above notations from the tobacco account book show how extensive the tobacco operation was at Lone Jack, but it did not seem to gain fame and hold on to it as the Shawhan Whiskey did. There were several tobacco manufacturers in Lone Jack before Shawhan. In fact, he had bought the business from Hedrick & Co.

"The books show that shipments of whiskey were made to several places in Kansas - Paola, Pleasonton, LaCygne, Trading Post and Council Grove, and perhaps many a keg of Shawhan whiskey was smashed by Carrie Nation.

"Ten gallons of peach brandy were shipped to I.N. Keler,2 Shawhan Station, Ky., October 19, 1881, and paid with dogs on May 1, 1882. Doctors and druggists in the area kept barrels of Shawhan Whiskey on hand, and one druggist in Oak Groe lost some of his to burglars one night. Although he had other brands, Shwhan was the only barrel drained, 'which says something for its quality,' reported a local paper.

"The Shawhans can trace their family back to 350 A.D. and beyond. In their genealogy book is written "The Shaughen family is descended from Milsius, King of Spain, through the line of his son Heremon. The founder of the family was Feachra, son of Enoch May Veagon, King of Ireland, 350 A.D." And somewhere down the line is Robert the Bruce, Robert I (1274-1329) King of Scotland. Incidently Robert was one of my favorite historical figures when I went to elementary school. It was he who hid in a cave while his pursuers were hunting him. He watched a spider build a web over the cavern mouth and took his perserverance from it. And the pursuers seeing the web across the cove said 'He is not in there.'

"James Shawhan of Lone Jack is a great-great-great grandson of the originator of Shawhan Whiskey. He and Mrs. Shawhan have given much help in the writing of this article. Other descendants in this area are Junior Shawhan, Lone. Jack; Rex Rowan, Kansas City, who also helped in this writing; Elizabeth Grubb and Wayne Shawhan, Oak Grove, and Harold Shawhan, Buckner.

"Mrs. Shawhan, writing for the Jackson County Historical Society, Dec., 1965, gave the following information: "Steam furnished the power for the distillery, and water was drawn from a large pondSept. 19, 1 1880, while apple jack was being made, the still blew up. A coil became stopped up with the apple pumace, and when Daniel Perrow increased the boiler pressure to clear the coil, it exploded. Perrow, his son, Will and Tommie Lester were killed. Six others were seriously injured. Twenty years later in January, 1900, at midnight the distillery caught fire and burned. The fire was caused by a defect in the wall around the boiler. At that time there were 800 barrels of whiskey in the warehouse" which did not burn.

"George Shawhan did not attempt to rebuild. He went to Weston, Mo. and purchased the Holladay distillery, and moved his family there.

"Mr. Shawhan had a high grade herd of Jersey cattle, with which he took several prizes at the Chicago World's Fair. One of his cows carried off nearly all the prizes offered at state fairs at the turn of the century and was the first cow west of the Mississippi River to take first prize at a world's fair. The Shawhan herd contained 49 high grade cows which were fed on mash from the distillery..."the greatest cattle food in existence" the Kansas City Journal, June 27, 1901 declared."

The Shawhan Bardstown, KY Distillery

The Shawhan Bardstown, KY Distillery

A Shawhan descendant had found a California Thrifty Drug Store, in the 1970s, that was selling a whiskey brand called "Old Miner", that came from the Shawhan Distillery of Bardstown, KY.

In our research, we were able to contact Sam K. Cecil, of Bardstown, KY. Sam is a retired distiller who has spent all of his eighty-odd years in Nelson County, other than when he was in the Army for five years during WWII. In particular, he has worked with distilleries in the Bardstown area. Much of what follows is based on what this good Kentucky gentleman shared with us:

George Henry Shawhan sold his Weston, MO distillery and Shawhan brand name, absent the Shawhan family formula, to the Singer family in about 1908. In some manner, the Shawhan name was eventually sold to Tom Pendergast, a member of the Kansas City Pendergast political machine the same political organization that was so helpful in the career of Harry S. Truman.

The advent of Prohibition in the 1920s put a stop to all such distillery

operations, except for a very few who were permitted to operate and distill for

medicinal purposes. At Prohibition's end, in the early1930s, a group of local

Bardstown, KY investors started the Independent Distillery in Bardstown, on the

site of the old Sam P. Lancaster Distillery They were unable to finance it

properly, and, in 1936, they sold out to Tom Pendergast who changed its name to

"Shawhan Distillery". The plant was subsequently acquired by Joe Makler of

Chicago; he continued to operate the facility in agreement with Waterfill &

Frazier Distillery, one of the larger distilleries in Kentucky. Waterfill and

Frazier made private brands, such as Thrifty Drug Store's "Old Miner", for

shipment to McKesson Robins Liquors in Kansas City McKesson Robins was a whiskey

supplier for Thrifty Drugs. Makler, together with Waterfill and Frazier, was in

this business until about 1974, when they transferred the Shawhan Distillery

label to Barton Distillery, another  Bardstown

company Barton also operated under the trade name of County Line Distillery. At

the same time, Makler sold the distillery plant location (private brand, the

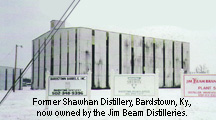

Shawhan Distillery) in Bardstown to the James B. Beam whiskey people, a

subsidiary of American Brands American Brands has since become Fortune Brands.

Beam tore down the distillery plant, but has retained the large warehouse.

Barton Distillery continued to supply McKesson and Robins with the Shawhan

Distillery private brand label of "Old Miner" for some years after 1974; it was

"bottled in bond" i.e. it was aged a minimum if four years and no more than

eight years and was 100 proof. Note: Sam Cecil obtained some of this data from a

friend of his, the former bottling superintendent of Barton Distillery.

Bardstown

company Barton also operated under the trade name of County Line Distillery. At

the same time, Makler sold the distillery plant location (private brand, the

Shawhan Distillery) in Bardstown to the James B. Beam whiskey people, a

subsidiary of American Brands American Brands has since become Fortune Brands.

Beam tore down the distillery plant, but has retained the large warehouse.

Barton Distillery continued to supply McKesson and Robins with the Shawhan

Distillery private brand label of "Old Miner" for some years after 1974; it was

"bottled in bond" i.e. it was aged a minimum if four years and no more than

eight years and was 100 proof. Note: Sam Cecil obtained some of this data from a

friend of his, the former bottling superintendent of Barton Distillery.

Note: In 1998, the Jim Beam warehouse location is still located and is utilized in Bardstown, KY.

THE BOURBON INDUSTRY IN 1998

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This narrative would not have been possible without the assistance and cooperation of many people. In particular the author would like to thank Mildred and the late James B. Shawhan of Lee's Summit, Missouri, who have been so gracious in sharing documents and stories about the Shawhans in Lone Jack and Weston. Also, a special thanks to Zac Shawhan II, Spencer Shawhan, Betty Shawhan Deterding, and Jane Shawhan Krusor for their invaluable assistance in bringing the Lone Jack and Kansas City, Missouri, Shawhan history alive for the greater Shawhan family.

ENDNOTES

1 "During the same period of time, names of other whiskey distillers crop up, and many of them have faded into obscurity. Such men as William Calk, Jacob Meyers, Joseph and Samuel Davis (brothers), James Garrard and Jacob Spears are mentioned in various documents, but either their families didn't follow in their footsteps or, if they did, their products weren't good enough to become long-lasting brand names of whiskey." (Gary Regan and Mardee Haiden Regan, The Book of Bourbon, Shelburne, Vermont: Chapters Publishing Company, 1995, p. 30)

2 Probably "Keller."