|

In the March 24, 2009, edition of SOTW, Robin threw down the literary

gauntlet by writing that:

“Minnesota has a somewhat dubious reputation in

my mind as providing the greatest number of ambiguous shots -- as in,

are they pre-pro or post-repeal? No doubt we've all been suckered into

buying what looks like a pre-pro glass from Minnesota (and billed as

such by the seller) and then discovering that in fact it's from the '40s

and thereby worthless. |

|

Hennepin Avenue, Minneapolis:

A Shot Glass Mecca or Morass? |

|

I also think of Minnesota as being the state that gave us the

greatest number of instantly forgettable glasses, most of which

originated from Minneapolis. No doubt Dick Bales will be spurred to

prove me wrong in a future edition of The Common Stuff.”

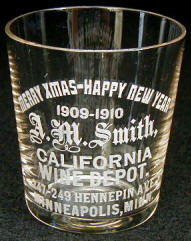

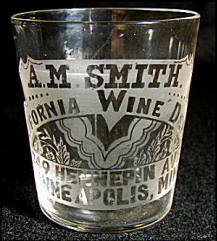

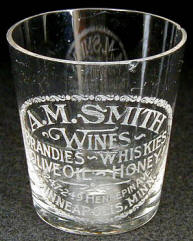

I will admit that Robin has a point (yes!! Ed.). For example, he mentioned the

Davis Mercantile Co.,

California Wine House, and

Dryer's Wines and Liquors glasses

as examples of snoozer shots. But he conveniently failed to

mention the highly collectible A.M. Smith glasses of 247-249 Hennepin

Avenue, Minneapolis

Robin

writes in his database that Andrew M. Smith was born in Denmark.

He opened the first California Wine Depot in Salt Lake City, Utah and

then moved to Philadelphia. Smith set up the Minneapolis branch in 1886

and closed the others. Smith died in 1915 but his son, Arthur Mason

Smith subsequently took over the business.

|

But there are more shot glasses that bear the Hennepin Avenue name than

just the A.M. Smith glasses.

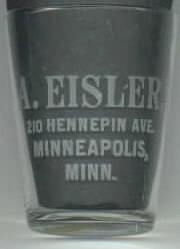

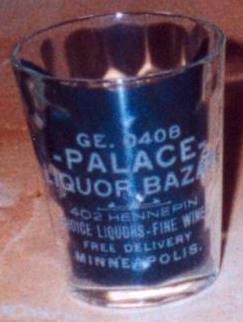

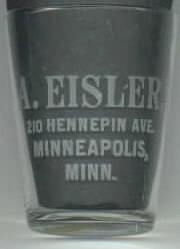

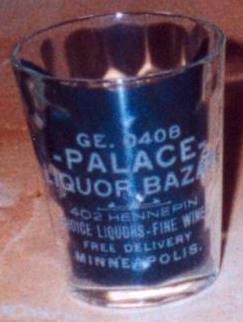

Consider, e.g., the A. Eisler glass (210

Hennepin) and the Palace Liquor Bazaar glass (402 Hennepin). |

|

Indeed, in keeping with the “Common Stuff” theme of this column, one

could devote a large amount of effort (and perhaps not too much cash) in

collecting just “Hennepin Avenue” shot glasses.

Contrary to Robin’s snobbery, such a pursuit would be a glorious one.

Although Minneapolis was incorporated in 1872, Hennepin Avenue (named

after Father Louis Hennepin, a Roman Catholic priest and an early

explorer of the interior of North America) dates back to the 1860s. Even

then, this right-of-way was the commercial center of the city.

Historians have dubbed the period from 1865 to 1890 as the “boom and

bloom years.” Bridge Square, at the foot of Hennepin Avenue, comprised

the area from Hennepin Avenue to Nicollet Avenue and from Washington

Avenue to the river. This square became the center of commercial and

civic activities.

The painting by Robert Koehler

(at right), “Rainy Evening on Hennepin Avenue,”

circa 1902, depicts the beauty of this thoroughfare at around this time. The painting by Robert Koehler

(at right), “Rainy Evening on Hennepin Avenue,”

circa 1902, depicts the beauty of this thoroughfare at around this time.

But by the end of the century, the business center of town began moving

from Hennepin Avenue to Nicollet Avenue. The avenue was facing its first

decline. Coming to its rescue and shaping Hennepin Avenue’s character

for the next fifty years was entertainment, vaudeville and theater. In

1886 (the year Andrew M. Smith set up shop), a traveling minstrel show

featuring Jo-Jo the Dog-Faced Boy drew a crowd of 8,000 people. A decade

or so later, theaters became the focus of Hennepin Avenue. Throughout

the 1920s, the avenue played host to all the so-called “greats” of

vaudeville—Al Jolson, Burns and Allen, and the Marx Brothers. Patrons of

the legitimate stage houses came to Hennepin Avenue to see Lillian

Russell, Ellen Terry, and Sarah Bernhardt.

On the postcard shown above, note that there is a theater on each side of

Hennepin Avenue. The names “Burns and Allen” appear on the marquee of

the Orpheum Theater, which is on the left side of the avenue, at 908-910

Hennepin. The photograph, taken in around 1925, shows another view of

this theater.

But 1929 brought the Depression, and Hennepin Avenue again fell from

grace. One account indicated that the avenue had become, by the end of

the 1920s, a “tumble down collection of cheap movie houses and

restaurants, squalid flop houses, penny arcades and pawn shops.”

The 18th Amendment (1920) banned the sale, manufacture, and

transportation of alcohol. Prohibition lasted until 1933, when the

ratification of the 21st Amendment repealed the 18th Amendment. A

so-called “syndicate” delivered liquor to speakeasies up and down

Hennepin Avenue during this time. One oldtimer named Eddie Schwartz

recalled a potion, “Minnesota 13,” so powerful that he wondered, “how

the glass could hold it.”

Hennepin Avenue has achieved iconic status in present-day Minneapolis

culture. It was prominently featured in the Prince movie “Purple Rain.”

It has been memorialized in songs by Tom Waits and Lucinda Williams. The

Orpheum Theater still stands, a testament to the tenacity of a gritty

street that refused to die. Hennepin Avenue lives on, as evidenced by

both this theater and its shot glasses.

|

The painting by Robert Koehler

(at right), “Rainy Evening on Hennepin Avenue,”

circa 1902, depicts the beauty of this thoroughfare at around this time.

The painting by Robert Koehler

(at right), “Rainy Evening on Hennepin Avenue,”

circa 1902, depicts the beauty of this thoroughfare at around this time.