In recent months I have been conducting some Civil War research for a book I am writing on the infamous Chicagoan, George Wellington "Cap" Streeter. (For more information, check out

www.capstreeter.com.) Bertram Hawthorne Groene writes in Tracing Your Civil War Ancestor about how researching the story behind an article like a Civil War sword gives it a pedigreed. He suggests that knowledge of an item can even increase its value.

I remembered Groeneís words when I saw a Chapin and Gore glass on eBay

(below). I quickly started to do some research, and was amazed at all I uncovered. The story I am about to relate here may not make this glass more valuable, but it does make the shot glass a lot more interesting! |

Desperate

Housewives

and

Shot Glass

Research:

An Affair to

Remember? |

|

|

Incidentally, I was the ONLY bidder for

this $9.95

glass. Sure, the glass doesnít look like much, but I bet that the following story is a better tale than the story behind a Foustís label under glass! |

In the early 1850s, Gardner Spring Chapin, a broker in mining stocks,

met James Jefferson Gore, who was running freight overland to Nevada.

Gore, who was sick and in need of money, asked Chapin for a $200 loan so

that he could travel on to Nevada. This $200 loan was the beginning of a

lifelong friendship. Chapin moved to Fairbault, Minnesota, where he

opened a dry goods store. After this business venture soured, he moved

to Chicago and established a grocery store on Madison Street. Meantime,

Gore had become a successful businessman, and he traveled to Chicago to

seek out Chapin. In 1865 they opened a grocery store at the corner of

State and Monroe streets. Gore convinced Chapin to add a liquor

department to the store, and soon liquor was their main enterprise. On

the eve of the Great Chicago Fire, they put out their own brand which

they called, "1867."

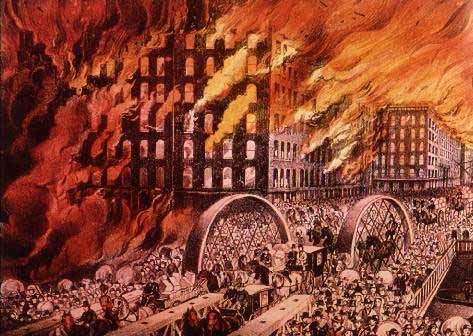

The day is October 8, 1871. On that Sunday evening, a fire started in Mrs. OíLearyís barn. (No, it was not the cow kicking over the lantern. To read about what really happened, go to

www.thechicagofire.com.) That summer had been horribly dry, and the fire soon spread out of control. Legend has it that to save their liquor stock from looters, Chapin and Gore hired some men to roll several hundred barrels of whiskey, rye, and bourbon down to the cityís lakefront. But despite their best efforts to save their stock, a few dozen barrels didnít make it all the way to the shores of Lake Michigan, but instead ended up in the clutches of the city's ne'er-do-wells.

|

After the fire, Chapin and Gore moved their establishment to a series of addresses in and around downtown Chicago. But apparently these were never good enough. The two men wanted a building in which they could combine their warehouse and office space with a street-level retail store and bar, and so in 1904 they commissioned the architectural firm of Garden and Schmidt to build this impressive structure at 63 East Adams Street.

This firm was acknowledged as being one of the most progressive architectural firms of the early 20th century. This is how the Chapin and Gore Building has been described: "Working with architect Hugh M.G. Garden, Richard Schmidt demonstrated the aesthetic possibilities of the utilitarian building through the bold exterior expression of interior functions, fine brickwork, and decorative terra cotta." The Chapin and Gore Building has been listed in the National Register of Historic Places since 1979. |

This picture (circa 1904) of the bar in this building shows just how fabulous this structure must have

been:

But this is not quite yet the end of the story.

Many people probably know of Theodore

Dreiser, one of the foremost American novelists of the early 20th century. His first novel was

Sister Carrie, originally published in 1900 and later reissued in 1907. Much of this book is based on the real-life escapades of Emma

Dreiser, Theodore Dreiserís sister.

In 1893 Theodore Dreiser was working as a newspaper reporter in St. Louis. Meanwhile, Emma was in Chicago, where, after ending an affair with an architect, she begins another one with Mr. L.A. Hopkins, the forty-year-old cashier of Chapin and Goreís bar. |

|

Hopkins is married with an eighteen-year-old daughter. After being confronted by his wife, who finds him in bed with Emma, Hopkins takes $3500 in cash and $200 in jewelry from Chapin and Goreís safe and flees to Montreal with Emma. Hopkins eventually returns all but $800 to Chapin and Gore, who do not press charges. Hopkins and Emma go on to New York. Years later, Theodore Dreiser convinces Emma to leave Hopkins, who is by now unemployed and urging Emma to rent rooms to prostitutes. It seems clear that L.A. Hopkins is no Cary Grant, and so I suppose that Emma Dreiserís New York liaison with the Chapin and Goreís cashier is not "An Affair to Remember." It is, though, one of the more incredible stories associated with a shot glass!

|